HEALTH CRISIS: Israel's public hospitals facing collapse; Hadassah announces it will not receive any more COVID patients

Rise in serious, critical coronavirus cases has strained public health system; Pres. Rivlin calls for immediate government relief

Israel’s independent public hospitals are on the verge of collapse and in desperate need of funding to continue their fight against the coronavirus.

Last week, during a dramatic protest outside of the Finance Ministry in Jerusalem, the managers warned they will no longer be able to run their hospitals without help from the government.

COVID-19 continues to rage across the nation, with well over 1,000 patients in serious condition — the highest figure since the beginning of the pandemic in March.

And in the midst of this the country faces another crisis as Israel’s independent public hospitals say they won’t be able to continue unless the government provides more funding. Hospital directors say they are already short on qualified personnel while at the same time cannot even afford to pay current staff. Without sufficient support, they will be forced to go into emergency mode, providing only life-saving services, the directors claim.

Just yesterday, Director General of Hadassah Hospital Zeev Rotstein announced that the hospital will no longer accept COVID patients at Hadassah Ein Kerem, and that he will soon be forced to transfer current patients to other hospitals.

"As is well known, Hadassah's hospitals are in severe cash flow distress," he wrote in a letter to Hezi Levi, director general of the Ministry of Health. "All management's efforts to reach an understanding with the Ministries of Finance and Health on this issue have so far come to naught."

"As the stock of medical equipment and medicines dwindles, Hadassah will be forced to refer hospitalized corona patients to hospitals outside the capital."

Rotstein has been leading the charge in innovative solutions to fighting the coronavirus. His battles with the Israeli government are well documented in this Jerusalem Post article. He argued that independent public hospitals are treated like orphans, whereas the government-owned hospitals are taken care of by the state and the health funds.

“When we get into economic difficulties because of this emergency, we have to ask for donations, whereas the government hospitals get payments from the state. It’s absurd,” Rotstein said.

In the protest last week, other hospital heads spoke out.

“We are struggling to survive. As we face both regular patients and corona, we are collapsing,” Prof. Ofer Marin, the director of Shaare Zedek Medical Center in Jerusalem said. “There are seven hospitals whose budget runs out every month. We aren’t paying suppliers, there’s no money for salaries. We have a simple request – distribute the money equally, but they are transferring billions to the government-owned hospitals. The Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Health figures show that these seven hospitals are run extremely well, but they are still punishing us.”

Dr. Prof. Fahed Hakim is the hospital director for the Edinburgh Medical Missionary Society (EMMS) Nazareth Hospital, Israel’s largest medical facility in the Arab sector.

“We are here on behalf of our staffs, who are looking the virus straight in the eye,” Hakim said. “We are soldiers without ammunition in a war that is a genuine war. Our soldiers — the medical teams —are not getting what they deserve.”

“We have reached the stage of threatening to move to emergency (mode) only because we have tried everything…everything,” he said. “We can’t pay wages, we have no medical equipment, we have no milk and the syringes are empty. We have devoted staffs who are working five times the normal amount during this emergency. 40% of my beds are taken by corona patients, but there are other emergency cases as well as corona.”

These three were joined by hospital directors in the same situation including Nadav Chen of Laniado Medical Center in Netanya; Prof. Ibrahim Harbaji of Holy Family Hospital in Nazareth; Shlomo Rothschild of Mayanei HaYeshua Medical Center in Bnei Brak; and Dr. Nael Elias of the Saint-Louis French Hospital in Jerusalem.

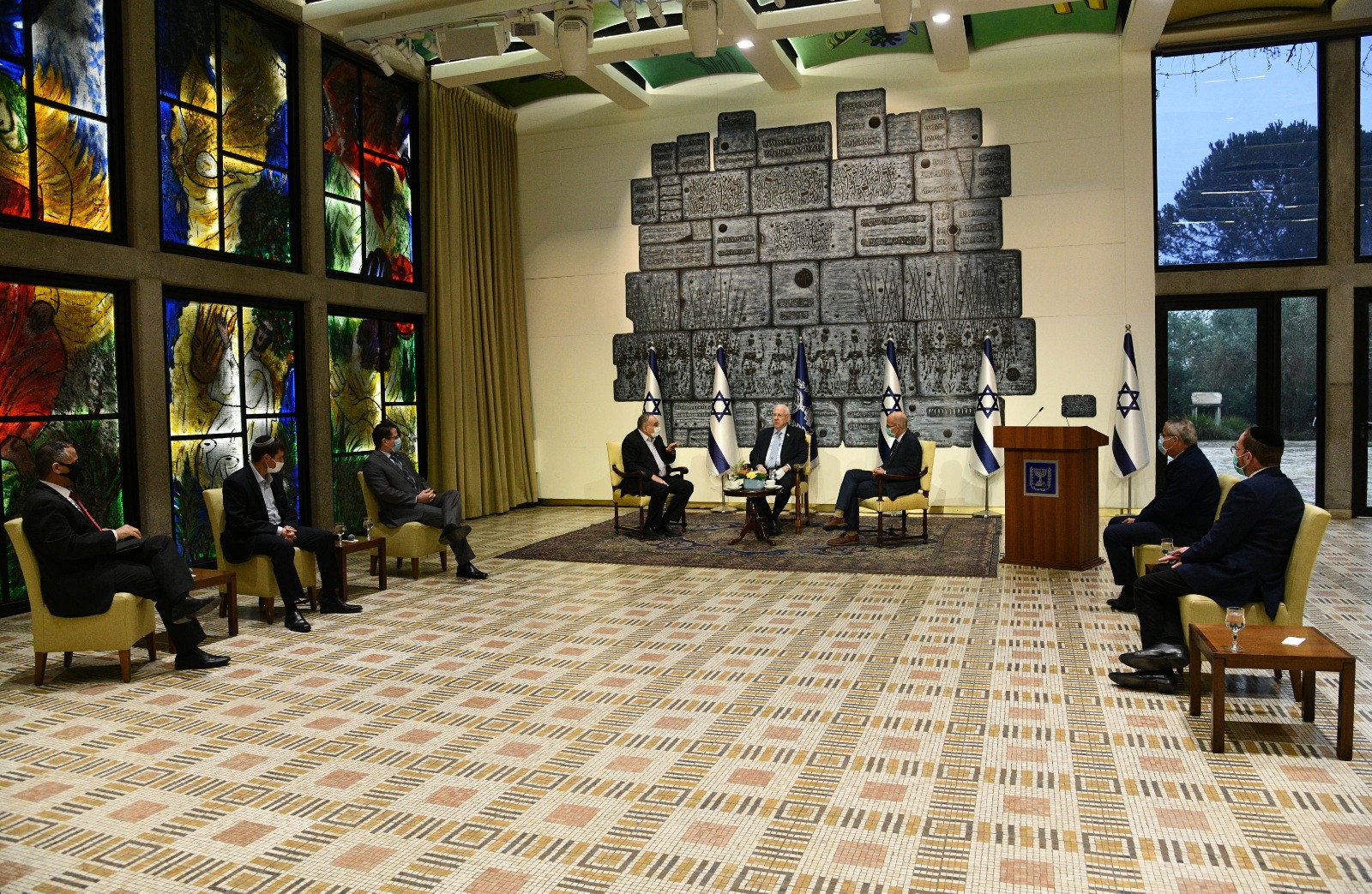

After meeting with the hospital directors, Israeli President Reuven Rivlin called on the ministries of finance and health to immediately resolve the budget crisis for these seven independent public hospitals currently treating Israelis with COVID.

“I know that you see yourselves as fighting for the future of your hospitals, for the future of public medicine. That is a just and right war, and I hope that the government has the wisdom to do what is required for you to survive the crisis,” he said. “That is our most basic obligation. You fight at the front and the government will supply the ammunition. There is no other way. We cannot win this battle without you.”

Israel’s healthcare system is based on a universal health insurance program, largely funded with taxes collected from its residents. Of the nation’s 44 acute-care hospitals, 11 are owned by the Ministry of Health, accounting for 47% of the national bed capacity. The employees are government workers and the hospitals’ budgets are controlled by the State of Israel.

Another nine public hospitals, which account for roughly 30% of hospital beds, are government-run and owned by one of Israel’s four health funds. Both government-owned and hospitals owned by the health funds follow a national hospital fee schedule and receive ongoing government funding. Physicians are mostly salaried employees, with limited arrangements for fee-based supplemental services.

The hospitals involved in the protest over the inequality of funding are independent public hospitals and are owned by non-profit organizations or set up as public-benefit corporations, like Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem. These nine hospitals account for about 17% of the national bed capacity.

In addition, the final 6% of beds are in 15 smaller hospitals that are either private or owned by a mission.

The National Health Insurance Law has never officially defined the government’s obligation to hospitals under the various ownership structures. This has essentially caused competition between the state — which is both the funder and system regulator — with other hospitals that depend on it for their budgets. Naturally, the state will favor its own hospitals which are more protected if they were to run a deficit.

While Israel’s independent public hospitals are struggling to adequately treat patients and pay staff, last year, the government assisted 15 countries across three continents to help combat the pandemic — providing equipment and supplies, technology and even a delegation of experts.

The coronavirus has brought to light a systemic problem deeply rooted within the Israeli healthcare system. The Taub Center for Social Policy Studies, an independent, impartial research institute based in Jerusalem, published a study last year in which it concluded that the general hospitalization system in Israel has systemic failures in planning, budgeting and government regulation.

The 47-page report published in December 2020, "The Battle Against the Coronavirus from the Perspective of the Healthcare System: An Overview," states, “…the Ministry of Health is responsible for managing the professional aspects of responding to a pandemic, including the operation of hospitals, clinics, and health offices; clinical and laboratory monitoring; preparing reference scenarios for an event; procurement and allocation of drugs and vaccines.”

Furthermore, the report states, “The coronavirus crisis is first and foremost a health crisis and the focus on protecting the healthcare services should be at the core of the fight in order to prevent a situation in which hospitals are unable to admit patients.”

Unfortunately, it appears that Israel has already reached that point.

The All Israel News Staff is a team of journalists in Israel.