Primer on the major Israeli political parties in the 24th Knesset elections

No clear pathway for any party as there are too many "chiefs" among "the 120 Indians" in Israel's parliament

As the nation heads to its fourth national election in just two years, despondent pundits are already forecasting a potential fifth electoral contest in the near future.

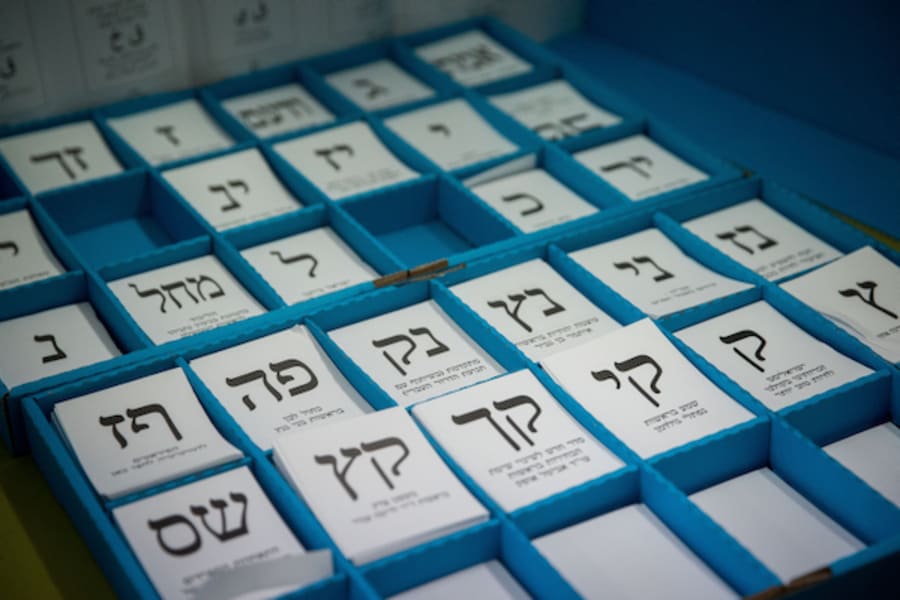

Ahead of each election in Israel, a plethora of new parties are formed. This time around, 39 parties have registered to be on the ballot. Yet usually only 10 to 15 parties are real contenders and have a chance of passing the electoral threshold of 3.25%. This article will give you an overview of the likely contenders for representation in the next Knesset (parliament), the 24th since Israel became a state in 1948, and also why it is so hard for them to work out a governing coalition.

The ultimate number in Israeli politics is 61 because this represents a majority of the Knesset’s 120 seats needed to form a government. The problem is that no one party ever wins this absolute majority on its own. Even the largest parties at best can hope for a windfall ranging from 30 to 40 seats.

Technically, it is also possible to form a minority government, i.e., a coalition with less than 61 Knesset seats, as long as the governing coalition does not face an opposing majority. However, this runs counter to Israeli political tradition.

Let’s look at each Israeli political party:

Likud

Netanyahu heads up the second-oldest party on the Israeli political scene. Founded in 1973 as a coalition of right-wing parties, the Likud espouses a nationalist-secular agenda with values that allow for a cooperation with religious parties.

Fiscally, the Likud has stood for limited government spending, extensive privatization and free-market reforms of the Israeli economy. This is very much the handiwork of Netanyahu, who served as finance minister under Ariel Sharon before winning the premiership in 2009.

The Likud signed the landmark peace deal with Egypt in 1977 and Netanyahu has continued this tradition by reaching peace agreements with several Arab states.

Natural political allies for the Likud are Shas, UTJ and Religious Zionism. Unlike the Likud, all these parties represent a certain identity and sector of the Israeli populace. The mandates from their constituencies are clear and these parties can be expected to support the formation of a right-wing government under Netanyahu but also to extract specific concessions for their role in doing so. The Likud has other parties that it can align with, but these have been alienated by Netanyahu’s leadership style and electoral bargains with the ultra-Orthodox parties.

Yesh Atid

Yesh Atid, who remained outside of the ill-fated national-unity government, has picked up the mantle as the leader of the centrist bloc. The party was founded by Yair Lapid in 2012, and seeks to represent the "center" of Israeli society, which it considers to be the secular middle class. Yesh Atid’s strength and weakness is that it focuses primarily on societal and governance issues from a secular angle. It sees itself as the champion of a secular middle class and fights to overturn privileges and political corruption. Yesh Atid, first and foremost stresses separation from the Palestinians, sidelining issues of sovereignty and annexation, except for Jerusalem’s status, which is to remain completely under Israeli sovereignty.

New Hope

Gideon Sa'ar recently founded New Hope – despite many years as a loyal member of Likud, he has outright pledged not to join a Netanyahu-led government. Gideon Sa'ar first challenged Netanyahu in an internal Likud party primary, which was handily won by the incumbent. Sa'ar subsequently decided to take the contest to the general public. His party has many concrete policy proposals, e.g., detailed changes for judicial reform and ideas aimed at making the every-day lives of Israelis easier in terms of their interaction with government bureaucracy. New Hope’s homepage contains one of the few holistic platforms with extensive policy issues and detailed policy proposals, addressing the areas where Israelis are hurting, such as housing and cost of living.

Yamina

Naftali Bennett, chairman of Yamina, on the other hand, has taken a more agnostic stance of working with Netanyahu. This is not because of love lost for Netanyahu, but rather with an eye to his party’s position in coalition talks following the next elections. Bennett was serving as defense minister during the beginning of the Corona crisis and has established an image and reputation as an effective operator. Bennett and his running partner former Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked, respectively religious and secular, have managed to combine the values of religious and secular nationalists but have yet to reach true breakthrough mass in terms of electoral results.

Shas

Shas is notable as an ultra-orthodox party that represents the large proportion of Israel’s Jewish population with Middle Eastern roots. Its foreign-policy stance is hawkish, while it emphasizes social justice for its relatively disadvantaged constituency. The party is led by co-founder Aryeh Deri and continues to work against economic and social discrimination against the Sephardic population of Israel.

United Torah Judaism

United Torah Judaism is the Ashkenazi counterpart to Shas, i.e. ultra-Orthodox Jews with roots in the European diaspora, United Torah Judaism is a coalition of two ultra-Orthodox parties, Agudat Israel and Degel HaTorah, officially formed in 1992 and currently led by Moshe Gafni.

United Torah Judaism seeks to preserve the religious character of the nation. Their policies support the interests of the ultra-Orthodox community, especially concerning welfare and education. They oppose the separation of religion and state, and the drafting of ultra-Orthodox men into the military. On foreign policy and the state of Israel’s borders, the party is centrist, in that it supported the 2006 Israeli withdrawal from the Gaza Strip. Both Shas and the UTJ have officially pledged not to form any government but with the Likud.

Religious Zionism

Two smaller extreme-right parties, Religious Zionism and Otzma Yehudit, led respectively by Bezalel Smotrich and Itamar Ben Gvir, have formed an electoral alliance for the 2021 March elections. Their cardinal issues relate to Israel’s stance on the West Bank, which they see as integral to Israel’s Jewish heritage and an indisputable part of Israel. They therefore do not accept any notion of territorial compromise. The parties are viewed as extreme but could win a combined five seats if they manage to maintain their momentum. Separately, they were almost guaranteed to fall below the election threshold, which would mean a loss to Netanyahu’s bloc of tens of thousands of votes, and which is why he is said to have been personally involved in forging the alliance between the two fringe parties.

Yisrael Beytenu

One party which has ruled out completely any Netanyahu-led government is Yisrael Beytenu, founded and led by Avigdor Liberman. Ideologically, this party is not far from the Likud, but appeals to a different demographic of immigrants from the former Soviet Union. Despite a certain ideological kinship, bad blood between Liberman and Netanyahu, as well as the Likud’s close association with the ultra-Orthodox parties’ cardinal interests run directly counter to Yisrael Beytenu’s core issues. In question are topics such as public transportation and the opening of stores on the Sabbath, as well as opposition to ultra-Orthodox exemption from military service.

Blue and White

Benny Gantz, former IDF Chief of Staff, broke a key electoral promise when entering into a coalition with Netanyahu, seeking to form a national unity government to guide Israel through the Corona crisis. Instead of gaining points for trying to govern responsibly, the party has lost much of its credibility with the electorate. In terms of security, the party’s platform does not differ too much from the Likud, in that the Jordan river was to form Israel’s security border and that no further disengagement should be undertaken, just as no division of Jerusalem was on the table. However, in terms of the religious nature of certain state laws, Blue and White sought accommodation for Israel’s secular public both in day-to-day living and civil marriage. Both of these ideas are hot-button issues for Israel’s ultra-orthodox parties.

Labor

Once the political home of statesmen such as Ben-Gurion and Yitzhak Rabin, Labor is fighting to stay relevant. Labor is a national party that has been reduce to a fringe party. The party stands out as being the only one captained by a female leader, Merav Michaeli. She was the one member of the tiny faction that refused to follow Amir Peretz and Blue and White into the National Unity government. This party used to be the anchor point of governance, but since the assassination of Rabin and a short stint in government under Ehud Barak in 1999-2000, the party has not been able to muster votes for a leftist agenda or offer a credible vision for Israel. The immediate goal for labor is electoral survival and Michaeli is choosing to do this through seeking to shape the tone in the anti-Netanyahu camp, rather than offer a grand alternative vision. The goal is to replace Netanyahu and what she labels “Netanyahuism,” characterized by a lack of respect for institutional integrity and rule of law. Interestingly, this makes her willing to sit with right-wing parties committed to ousting Netanyahu but opposed to her political goals, which include brokering a peace with the Palestinians.

Meretz

To the left of Labor is Meretz under Nitzan Horowitz, the first openly gay party leader in Israel. Beyond traditional leftist values, Meretz champions minority-rights of Arab citizens and calls for the end of “occupation.” Like Labor, it is a staunch supporter of the welfare state. Controversially, Horowitz has recently supported the ICC war crime probe into the IDF’s conduct during Operation Protective Edge in 2014, Israel’s settlement policies and confrontations along the border with Gaza in 2018.

The Joint List

Finally, Arab parties have since the raising of the electoral threshold to 3.25% in 2014, run together in an election alliance known as the Joint List, the unifying factor being the Arab identity. The Joint List currently polls at nine seats. The Joint List is largely sidelined in coalition politics because most parties do not want to build their government on Arab support, just as the Arabs are wary not to be seen as to in step with Jewish parties, but Arab parties did play decisive role in supporting Rabin’s government after defection by Shas in 1993.

The All Israel News Staff is a team of journalists in Israel.