Gaza through the ages: Tracing the historical significance of Gaza in Jewish heritage

The historical connection of Gaza to the Jewish people is multifaceted and complex, spanning multiple cultures and religions throughout history, from the biblical period to the modern era.

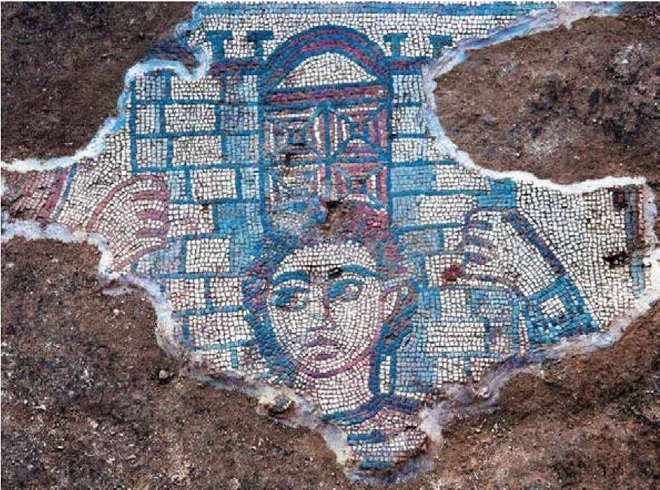

Gaza is one of the world's oldest continuously inhabited cities, with its history dating back over 3,000 years. Archaeological evidence suggests that the city was established around the 15th century B.C.E.

Originally a Canaanite city, it later came under Philistine control. According to the Hebrew Bible, Gaza was one of the five Philistine city-states and was often in conflict with the ancient Israelites.

Throughout its long history, Gaza has been ruled by various large empires, including the Egyptians, Romans, Byzantines and Ottomans.

One of the most famous biblical stories involving Gaza is that of Samson, a judge of Israel, who performed feats of great strength against the Philistines in Gaza, including his final act of bringing down the temple of Dagon, a Philistine god, upon himself and his captors (Judges 16:28-31).

During the Persian and Hellenistic periods, from approximately 550 to 330 B.C.E., Gaza thrived as a trading hub due to its strategic position on the coastal road between the territory of Israel and Egypt.

Later in history, when Gaza was under Roman and Byzantine rule, it was established as a prosperous city and a center for early Christianity. Despite this, there remained a Jewish presence in the city.

After the Crusader era, the Mamluks revitalized Gaza, transforming it once again into a bustling trade city. Between the Middle Ages and the 16th and 17th centuries, texts and illustrations that depicted Jewish holy sites were distributed across Israel and among Jewish communities abroad. Examples of these illustrated scrolls are now available at the recently opened National Library of Israel (NLI) in Jerusalem.

The documents are reproductions of the Yichus Ha’Avot scroll, the short reference for the full title: “Lineage of the Forefathers, Prophets, Righteous, Tana’aim, and Amora’im, May They Rest in Peace, in the Land of Israel and Beyond, May God Establish Their Merit for Us, Amen.”

Each scroll serves as a record of the holy lineage and revered figures in Jewish history, both within and beyond Israel, focusing primarily on the burial sites of ancient Jews. These include those buried in the Cave of the Patriarchs (Me’arat HaMachpela) and the tombs of the Amorites, which are located throughout the region and even beyond, such as the tombs of Mordechai and Esther from the Purim story and the tomb of the biblical hero Daniel.

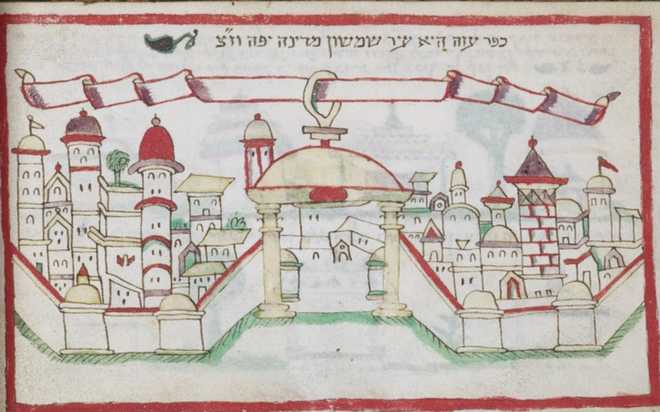

In one particular copy of the scroll originating from northern Italy in 1598, the following Hebrew inscription appears: “Kfar Gaza, the city of Samson, a beautiful country.” The accompanying illustration shows a walled city with numerous towers capped with domes, some suggesting mosques and others reminiscent of churches. The entire city is encircled by a wall, with a prominent domed gate without doors as the symbolic entrance to the city.

In another version of the Yichus Ha’Avot scroll dated to the 17th century, also part of the NLI collection, Gaza was envisioned as an oasis of sorts – lush with vibrant greenery and vividly colorful landscapes; mosques standing tall and majestic; and an impressive city gate without doors.

Not surprisingly, written records, archaeological evidence and various historical travel journals of Gaza suggest a different reality. Artists of the time frequently used their imagination to produce their inspired interpretation of geography, driven more by emotion and symbolism than accuracy. This artistic approach allowed viewers to feel as though they were walking in the footsteps of their ancestors and connected to the "lineage of the fathers."

The inclusion of Gaza as a holy site – a "beautiful country” and the "city of Samson” – is particularly of interest because it did not appear in early versions of the scrolls. Gaza was not considered one of the four traditional Jewish holy cities in Israel and various Jewish legal (halachic) texts even raised the question of whether Gaza should be considered part of the "Land of Israel" at all. If it were not, then Jewish religious commandments and obligations would not apply to those living in Gaza.

Despite Gaza not being deemed one of those four Jewish holy cities, it became a popular resting spot for pilgrims traveling to the Holy Land. The creators of the Yichus Ha’Avot scrolls probably understood that these travelers, including immigrants to Egypt from Italy, would pass through Gaza and be drawn to visit locations connected to religious figures and righteous heroes.

Therefore, the biblical hero Samson – known for his extraordinary strength and tragic fate in the city – became a way to highlight Gaza as a place rich in Jewish heroic history – providing a significant connection between Jewish people and Gaza, despite its lack of any notable tombs.

Some suggest that the reason the scroll artists depicted Gaza as a walled city with its gates wide open is to symbolize the destruction of the city’s gates by Samson.

“The illustrators of the scrolls didn’t illustrate Gaza, the prosperous trading city without a wall, but rather as a city whose doors Samson had uprooted, leaving it with wide open gates. That’s also why they call it the “Land of Samson,” according to the NLI. Known for his legendary conflicts with the Philistines, Samson is deeply embedded in Jewish scriptural and cultural history.

Later, after the Islamic conquest in the 7th century, Gaza became a part of the Islamic Empire. Throughout the Medieval Period, including during the time of the Crusades, Gaza's economic status fluctuated dramatically between poverty and prosperity due to conflict, changes in political control, and economic blockades. For example, when the Crusaders conquered the Holy Land, trade relations between the Kingdom of Jerusalem and Muslim Egypt came to a halt, leaving Gaza in ruins and largely abandoned. However, after the Mamluk conquest, Gaza was rejuvenated into a significant roadside trading city.

A Jewish banker from Italy, Rabbi Meshullam of Volterra, visited Gaza in 1481 and described it as a "good and fat land" with a thriving, albeit small, Jewish community that produced wine.

He also wrote: “Aza is called Gaza by the Ishmaelites, and it is a good and fat land, and its fruits are very fine. And there is good bread and wine, although the wines are only made by the Jews. Its perimeter is 4 miles long and it has no walls...it is surrounded by blue on the shore of the sea. And has about 60 Jewish homeowners...”

About 30 years later, in 1517, the Ottomans emerged victorious in their conflict with the Mamluks.

Ottoman Sultan Selim I captured the entire region, including the territory of Israel, the shores of the Red Sea, Mecca, Medina and Egypt. This victory boosted Gaza's strategic importance, transforming it from a marginal border city to a centrally-located city within a vast wealthy empire.

The Ottoman's victory led to the establishment of the Ottoman Empire and soon after all the major holy sites of Islam and Judaism, and most Christian holy places, were under the control of one regime. This ultimately led to secure travel routes for pilgrims of the major religions and a significant growth of Gaza's economy.

From the early 16th century until the end of World War I, the Ottoman Empire continued to govern Gaza, incorporating it into the administration of Damascus, now part of Syria. During this period, Gaza continued to serve as a trading and agricultural hub. Although the Jewish population was small, the area was considered part of the broader land of Israel by various Jewish communities.

After World War I, Gaza fell under British Mandate control, a period which lasted from 1917 to 1948. During this time, Gaza was administered by the British military along with the rest of the region. The region did not see significant development or immigration during this period, remaining mostly agrarian.

However, after Israel's War of Independence in 1948, the situation changed dramatically. Gaza came under Egyptian control and was not included in the newly established State of Israel. This period saw a surge of Palestinian refugees who had either fled or been expelled from their homes in what became Israel, significantly altering Gaza's demographic and economic landscape.

In 1967, Israel captured Gaza from Egypt during the Six-Day War, and it subsequently became a focal point of Israeli-Palestinian tensions. Over the next few decades, Israel established several settlements in the Gaza Strip. The area remained a hotbed of conflict, and the political landscape evolved with the rise of the Palestinian nationalist movement, including the formation of Hamas in 1987.

The Oslo Accords in the 1990s brought some administrative changes, but significant strife continued.

In 2005, under Prime Minister Ariel Sharon, Israel unilaterally disengaged from Gaza, withdrawing all Israeli troops and dismantling all Israeli settlements in the region in an effort to reduce tensions and improve security. Notably, Benjamin Netanyahu was then serving as Israel's finance minister and was a vocal critic of the Gaza disengagement plan. He argued that it would compromise Israel's security and provide a base for Palestinian attacks against Israel. His strong opposition prompted him to resign in August 2005, just before the withdrawal was implemented.

Now, nearly 25 years later, with Prime Minister Netanyahu at the helm, the Gaza Strip remains a continuous battleground for Israel, which seeks to defeat the Hamas regime, a designated terrorist organization that has controlled two million Palestinians in the coastal enclave for nearly two decades. A regime that advocates for the elimination of the State of Israel and rejects any peaceful solutions to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. A regime that planned and executed a terrifying invasion and horrific terror attack against thousands of Israelis living in southern Israeli communities near the Gaza border.

There is no denying that the city of Gaza has played a significant role in Jewish history, with its impact varying from good to bad, depending on the ruling powers.

Its portrayal as a place of beauty and biblical heroism, despite the absence of significant religious Jewish monuments, underscores its unique place in Jewish heritage and is sharply contrasted with its geopolitical context today.

Against this complex backdrop, the State of Israel, the United States, moderate Arab states and the rest of the international community now raise the question: Who will next rule the Gaza Strip when Hamas is defeated and what role will Israel play the ‘day after’ the war ends?

The All Israel News Staff is a team of journalists in Israel.